Letter from the director

Dear friends,

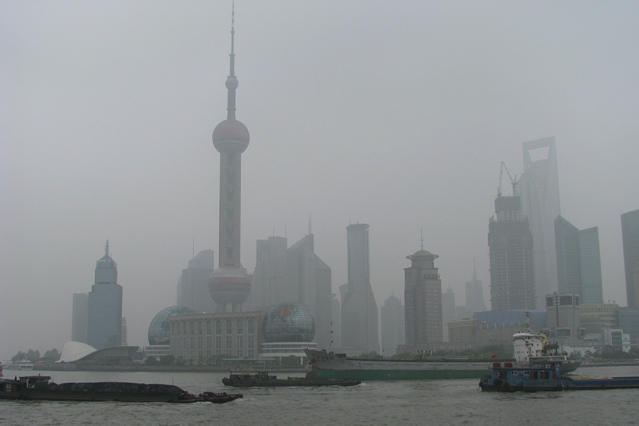

These are interesting and challenging times for energy. There are signs of emerging global action on climate change as we move toward the Paris meeting in December. In a joint announcement issued last November, China committed to capping CO2 emissions growth by 2030, and the United States pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2025. In addition, in late February, India committed to a major scale-up of both solar and wind power by 2022.

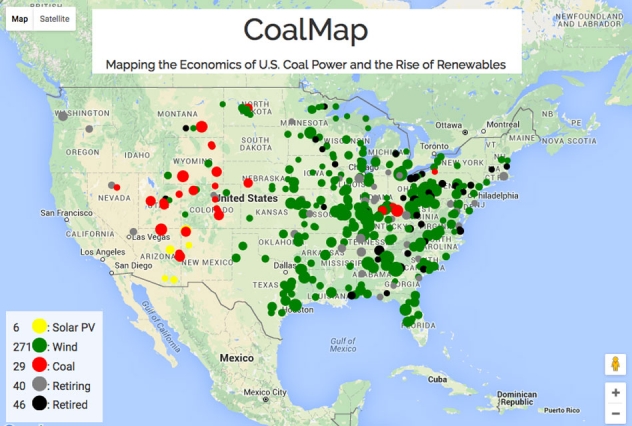

At the same time, existing businesses are being stressed. Oil prices are severely depressed relative to a year ago, in part due to industry success in bringing new technology to bear on producing shale oil. The electric utility industry is working hard to understand what business models will be like 10 or 15 years from now as distributed generation continues to grow, distributed storage begins to emerge, and the “internet of energy” provides new ways of increasing efficiency and reducing emissions. As we tackle such challenges, we find that the MITEI model of partnering closely with the energy industry and bringing together all of MIT’s schools is more valuable than ever.

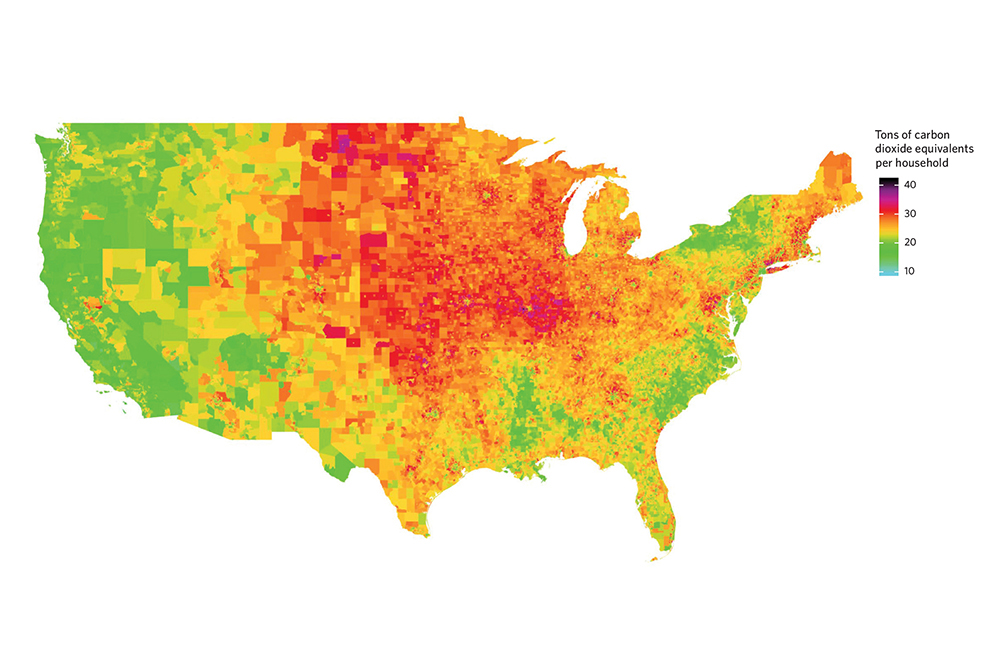

I see the energy challenge before us as having two parts: By midcentury, we must meet a projected doubling in energy demand—the result of growing global population and increasing standards of living. At the same time, we must dramatically lower the carbon emissions of our energy systems to mitigate climate change.

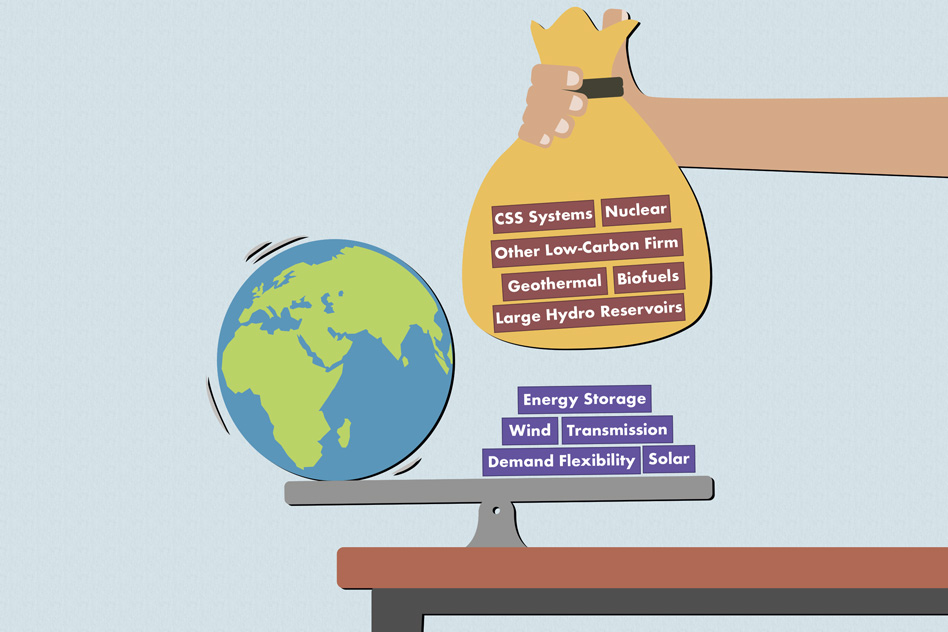

How can we double energy output while slashing emissions? I believe that five key technologies can help—and MIT is working on all of them.

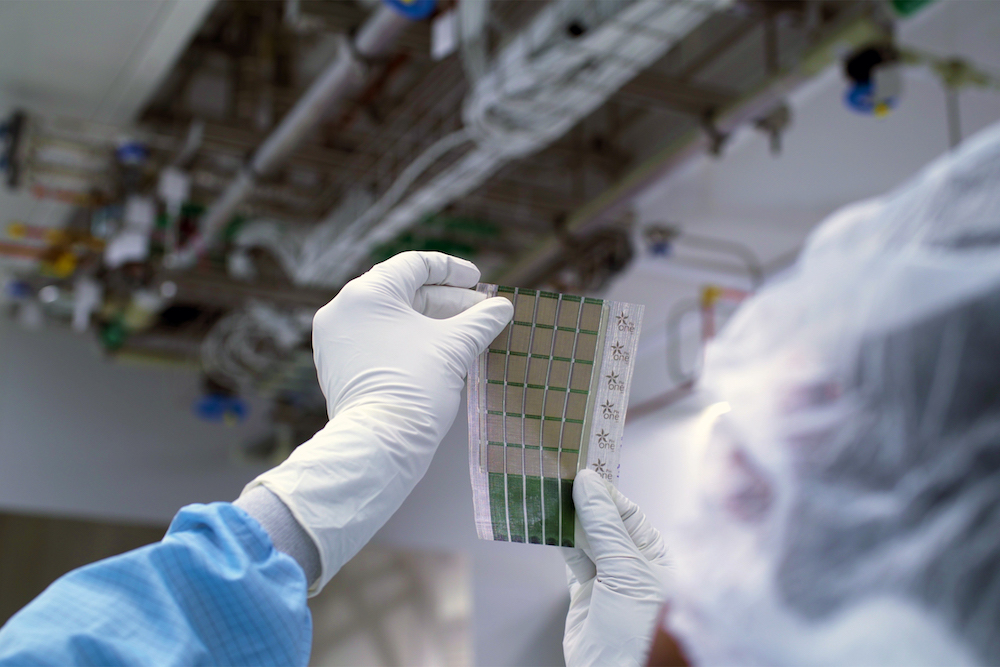

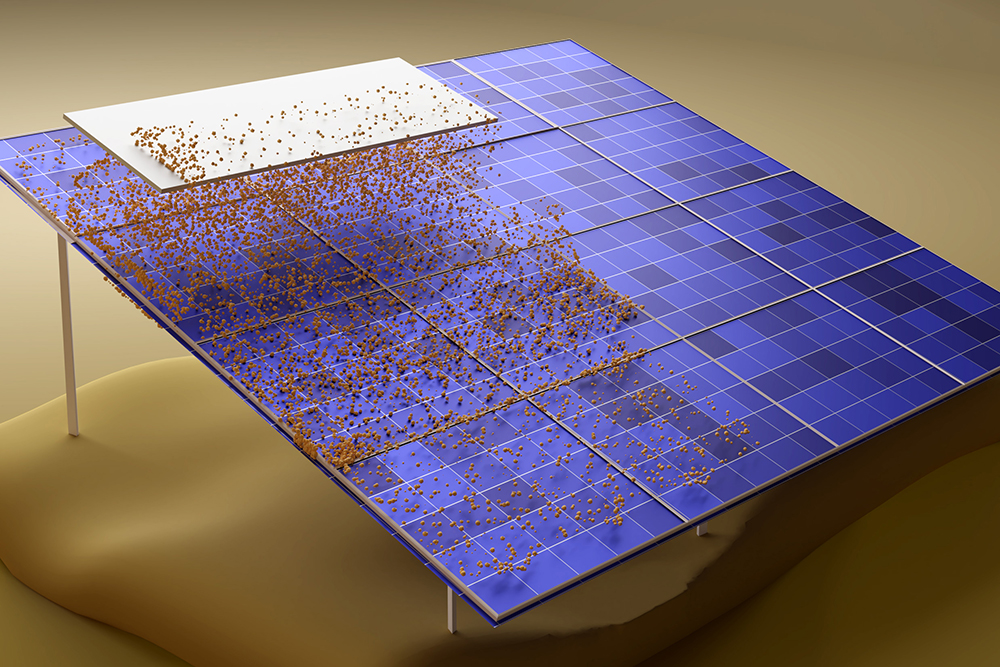

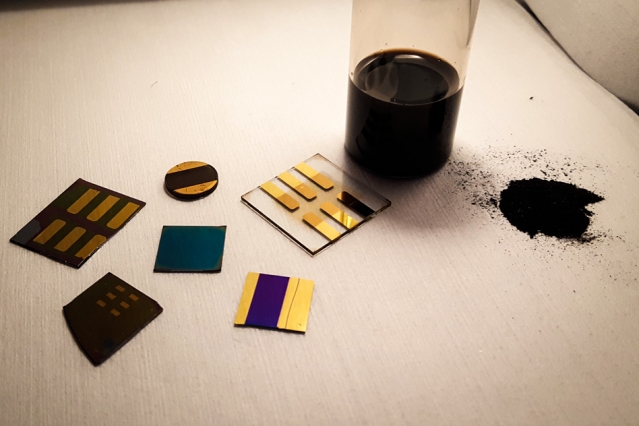

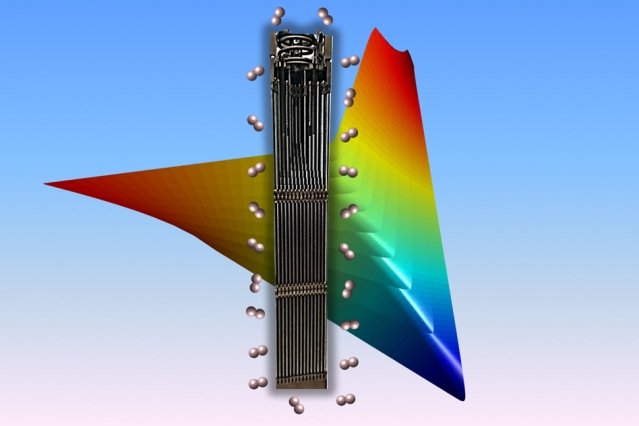

Solar is a vast resource for the world to utilize, and it will almost surely be critical to a sustainable future. We will have much more to say about solar in the next issue of Energy Futures when we report on “The Future of Solar Energy,” a comprehensive, multidisciplinary MIT assessment that was released in early May 2015.

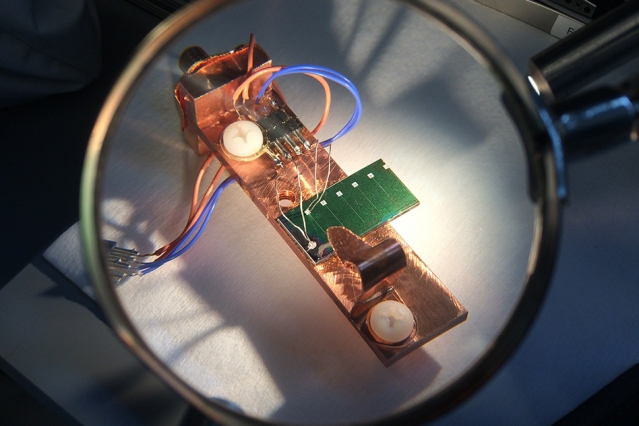

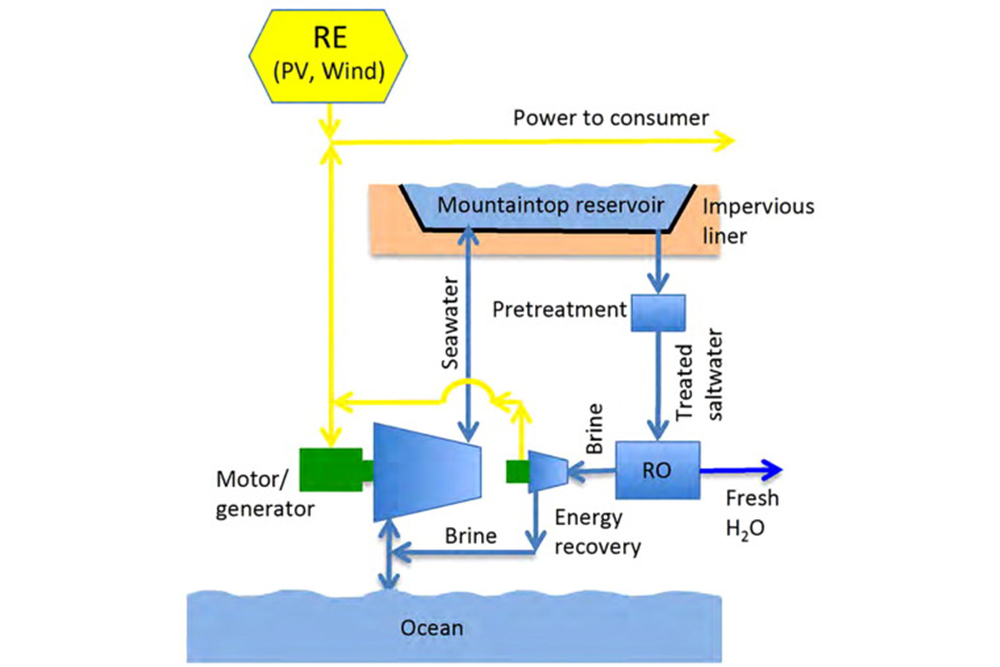

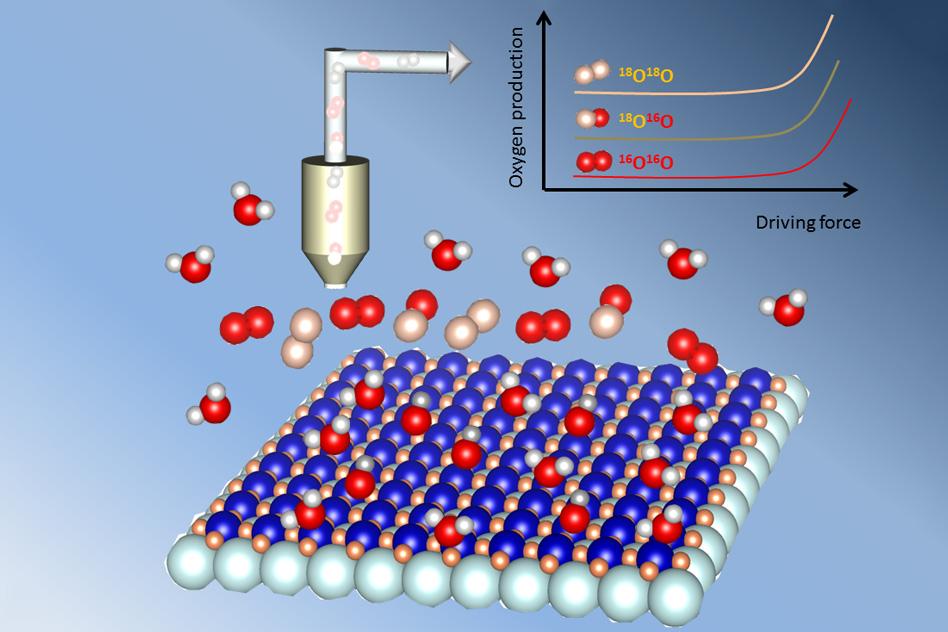

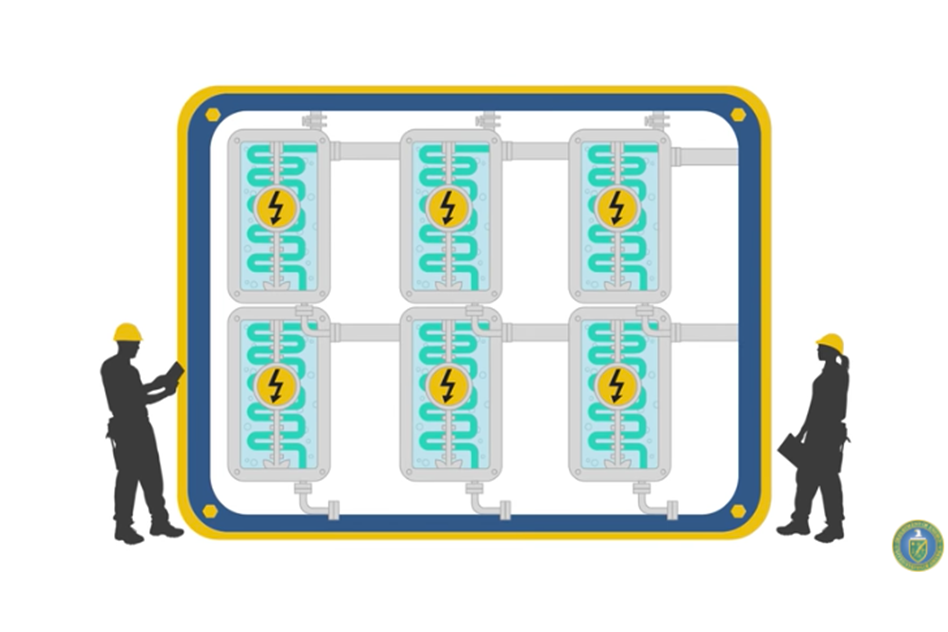

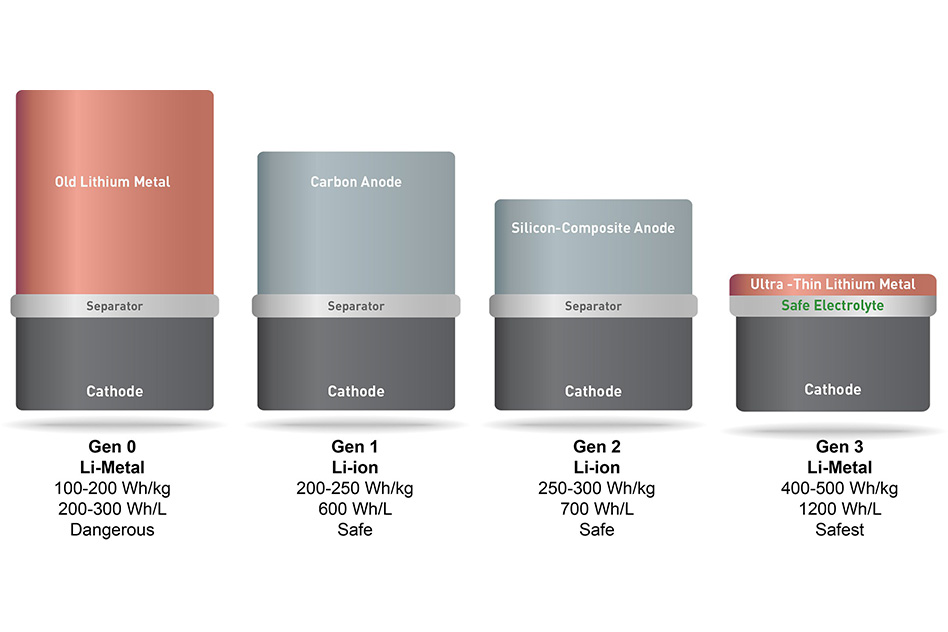

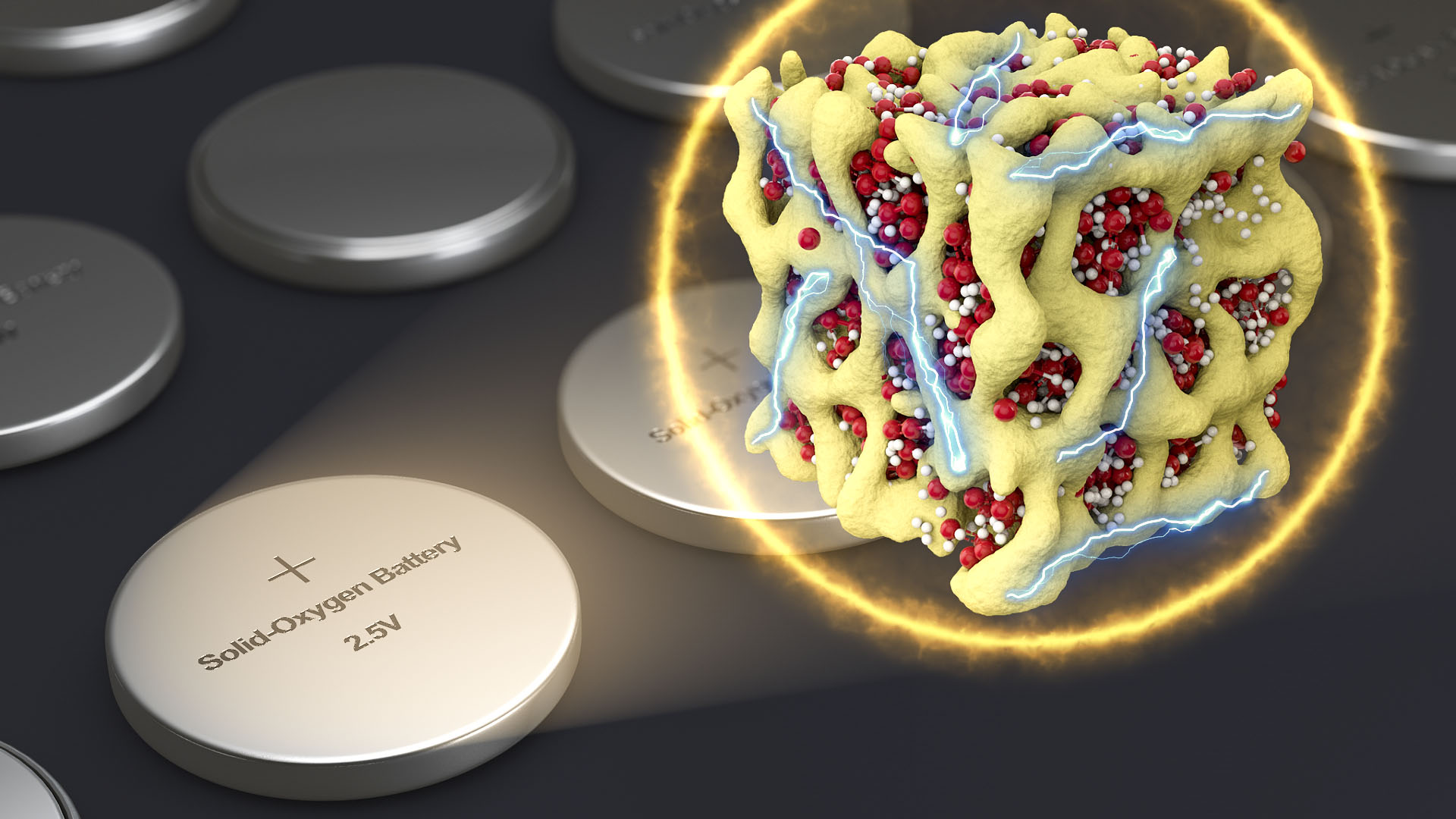

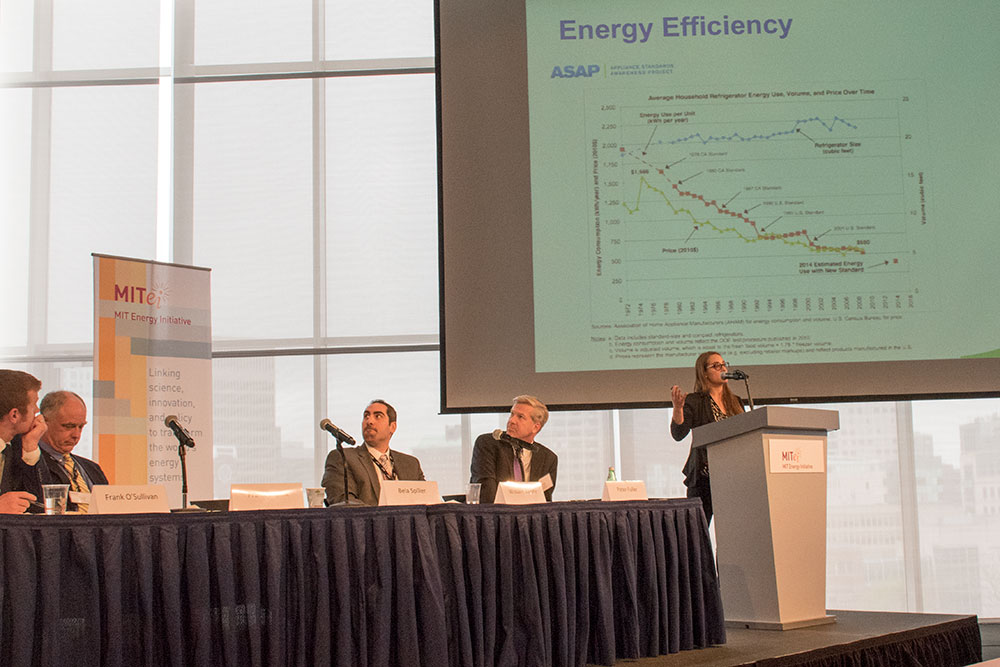

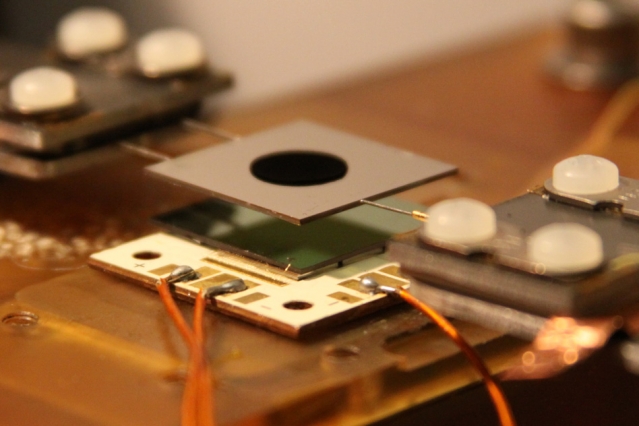

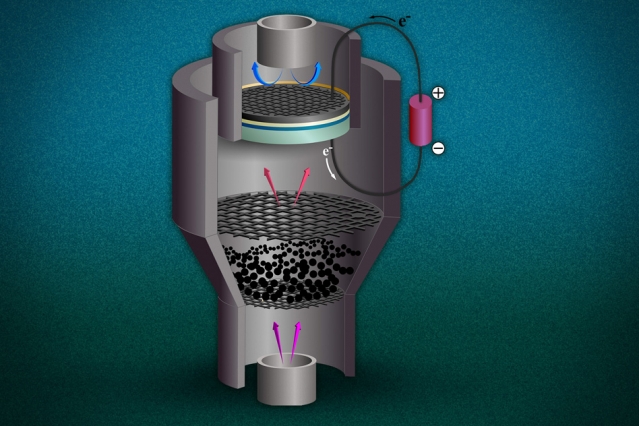

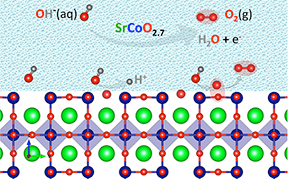

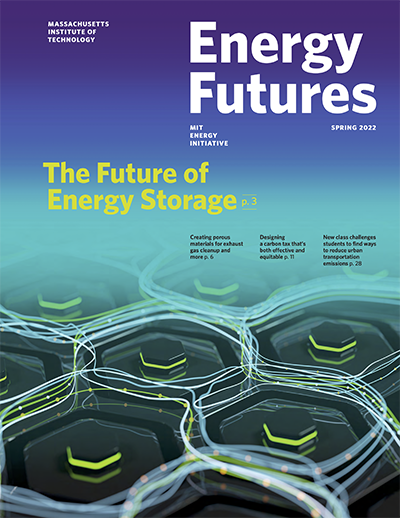

Energy storage is of interest for uses ranging from consumer electronics and vehicles to residential and commercial equipment. But perhaps most important is large-scale energy storage, which is critical for the successful incorporation of solar and wind generation into the power grid—the subject of a recent MITEI symposium, which gathered experts to discuss promising grid-scale storage technologies and related issues of regulation and market design.

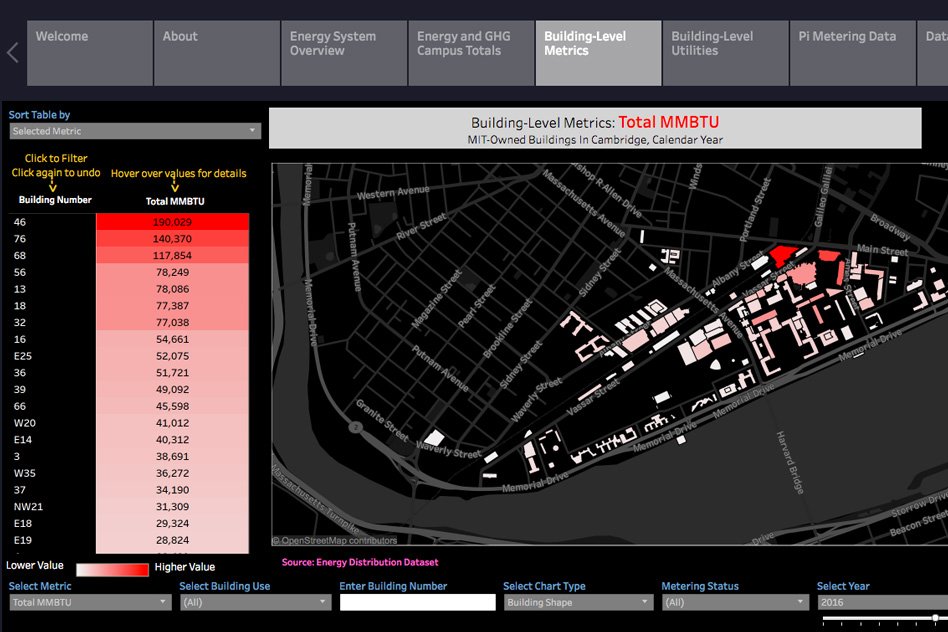

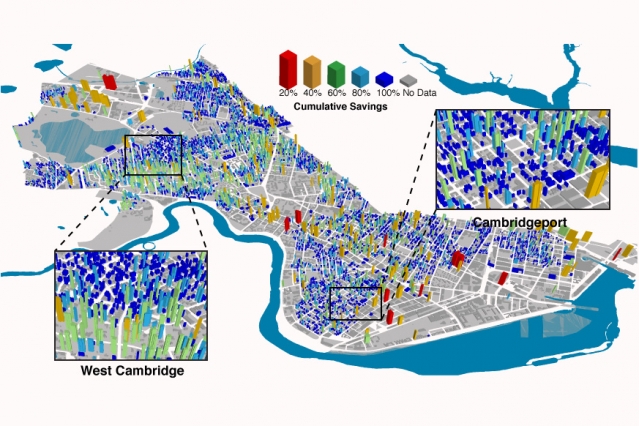

The power grid itself is clearly critical to our energy future. Research is needed to reimagine the architecture, size, reliability, security, adaptability, and resiliency of our current power system. Such issues are being addressed in our “Utility of the Future” study, an ongoing analysis that involves MIT researchers and a consortium of industrial and other stakeholders.

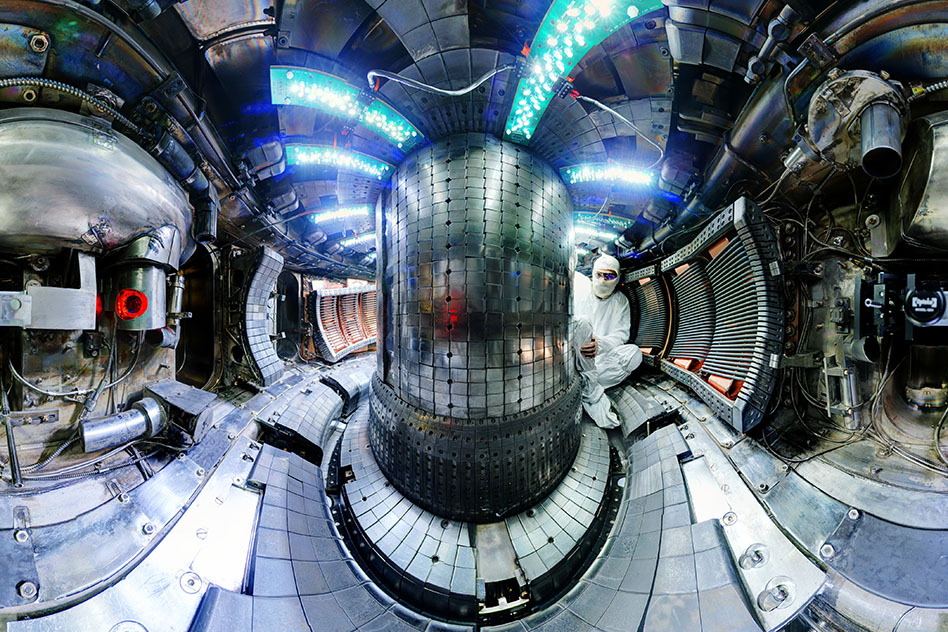

Nuclear fission is the only at-scale, zero-carbon energy-production technology we have ever used, but some countries are now limiting and even cutting back its use. It is hard to imagine a low-carbon future without nuclear, so we must address concerns about cost, public safety, security, and waste disposal. An article in the latest issue of Energy Futures reports on a novel MIT concept that tackles those concerns by floating a nuclear power plant at sea, where it is away from people, unaffected by earthquakes and tsunamis, and surrounded by an abundant, passive source of cooling water.

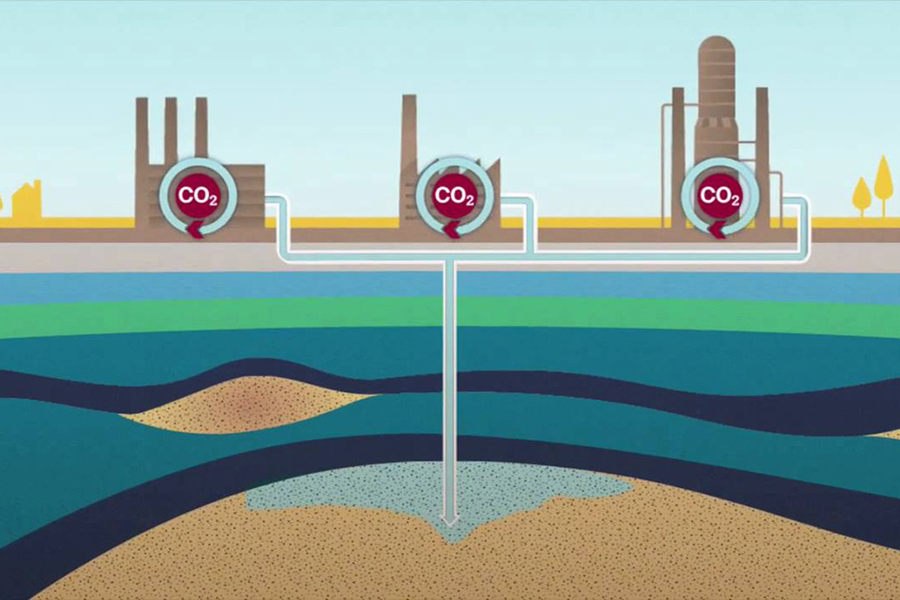

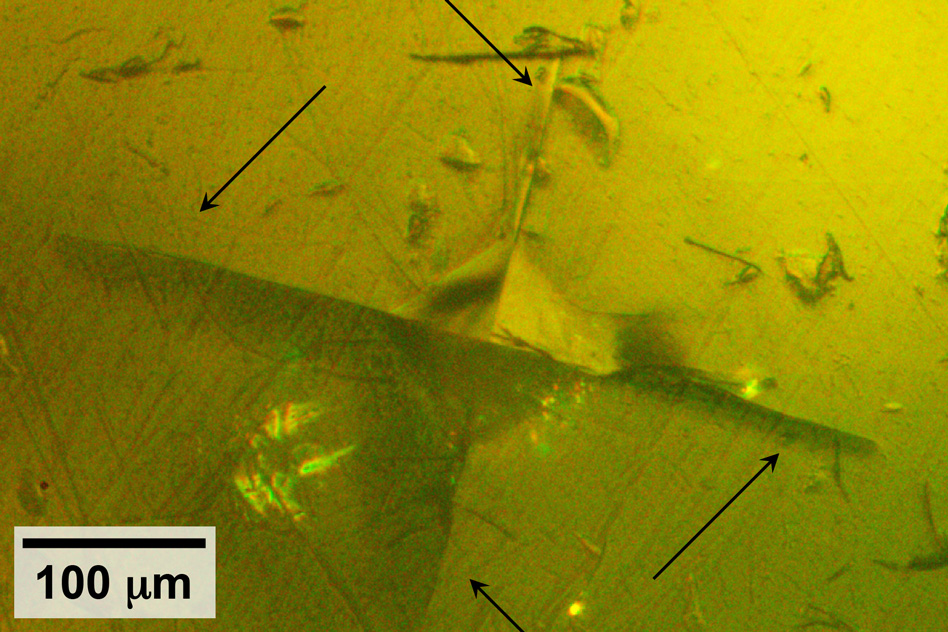

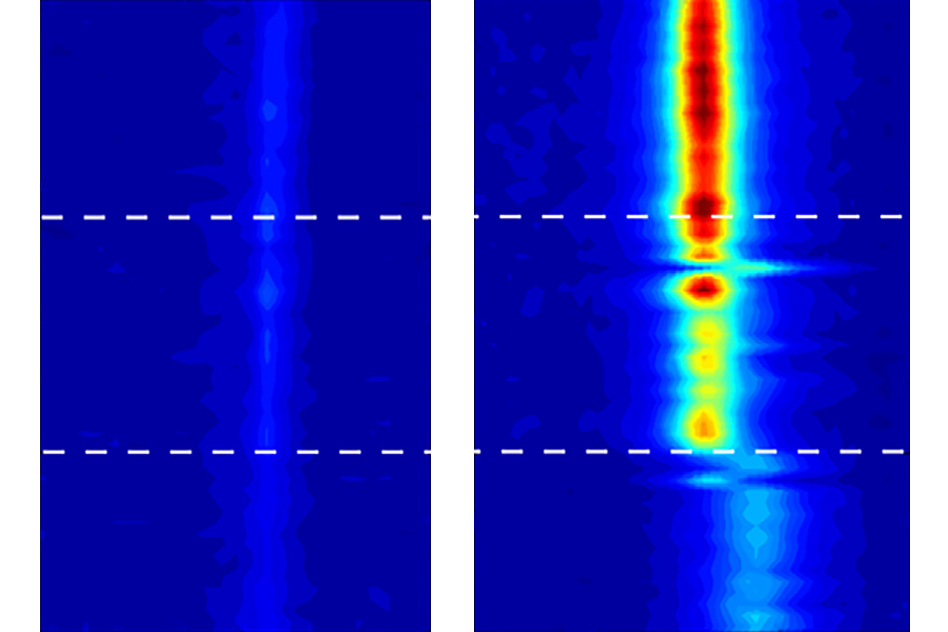

Finally, we will need carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). According to most projections, fossil fuels will continue to dominate the energy supply mix for the coming three or more decades. To protect the environment, therefore, we must capture the carbon released as those fuels are produced and used and sequester it deep underground. MIT researchers have been leaders in this critical area, developing new, low-cost capture systems, modeling processes that will trap injected CO2 underground, analyzing public policy designed to incentivize CCS, and more.

Taking full advantage of these and other promising technologies will require collaboration not only among researchers across the MIT campus but also among experts and stakeholders worldwide.

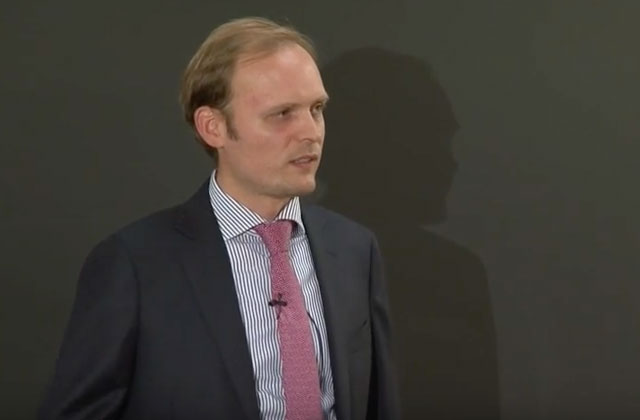

To that end, in February, I traveled to New Delhi, India, on behalf of MITEI to speak about clean coal technologies and natural gas-derived fuels at the 5th World PetroCoal Congress. India is the world’s third largest emitter of CO2; its main energy source is coal; and its population and economy are growing rapidly. Therefore, we cannot have a conversation about global energy solutions without India’s voice present.

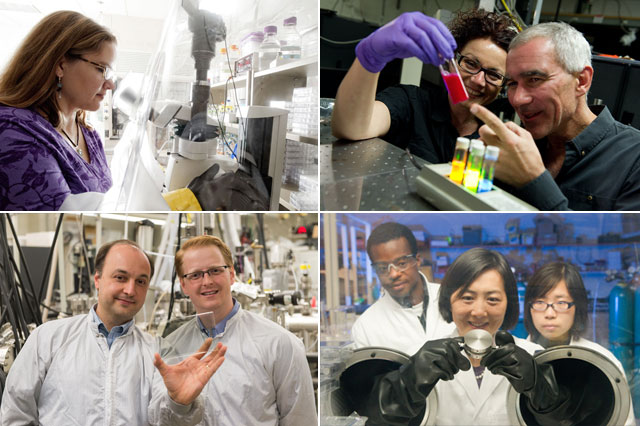

Meanwhile, MIT researchers continue the long-standing tradition of working with collaborators around the world. Two projects involving international cooperation are described in this issue.

In one, teams led by faculty from architecture are working with a nonprofit in India to create energy-efficient, earthquake-resilient, low-cost housing for rural regions of that country. The work takes place through MIT’s Tata Center for Technology and Design, which tackles a variety of challenges faced by resource-constrained communities in India and elsewhere in the developing world.

The second project involves collaboration between researchers at MIT and Tsinghua University in Beijing through the Tsinghua-MIT China Energy and Climate Project. China is now the largest emitter of CO2 in the world, and its emissions continue to increase. In this project, a CECP team has examined how new Chinese energy and climate policies can reverse the constant upward growth of those emissions—without a major impact on national economic growth.

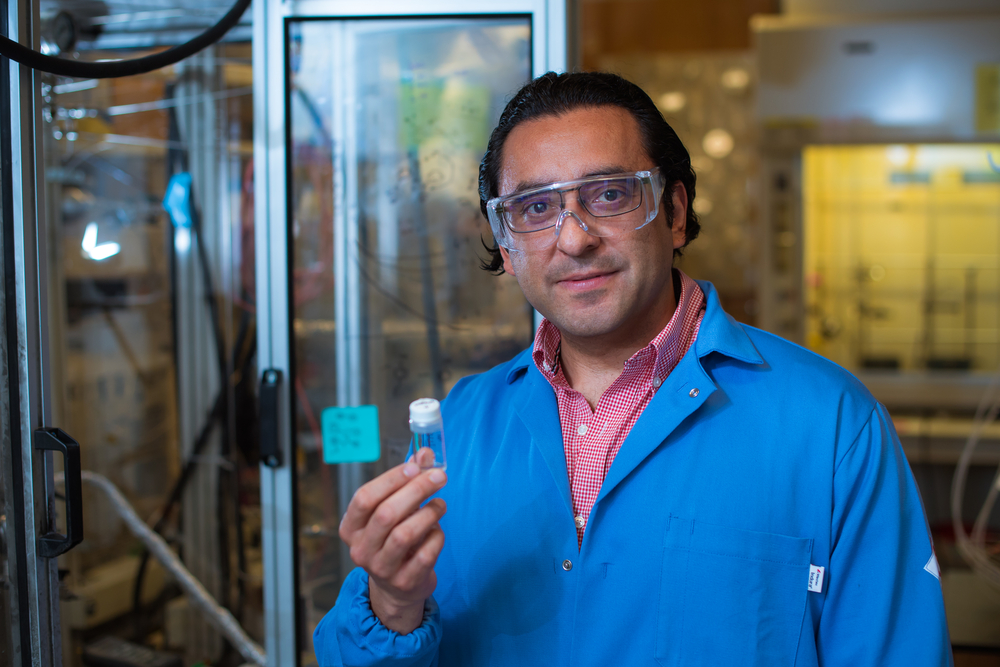

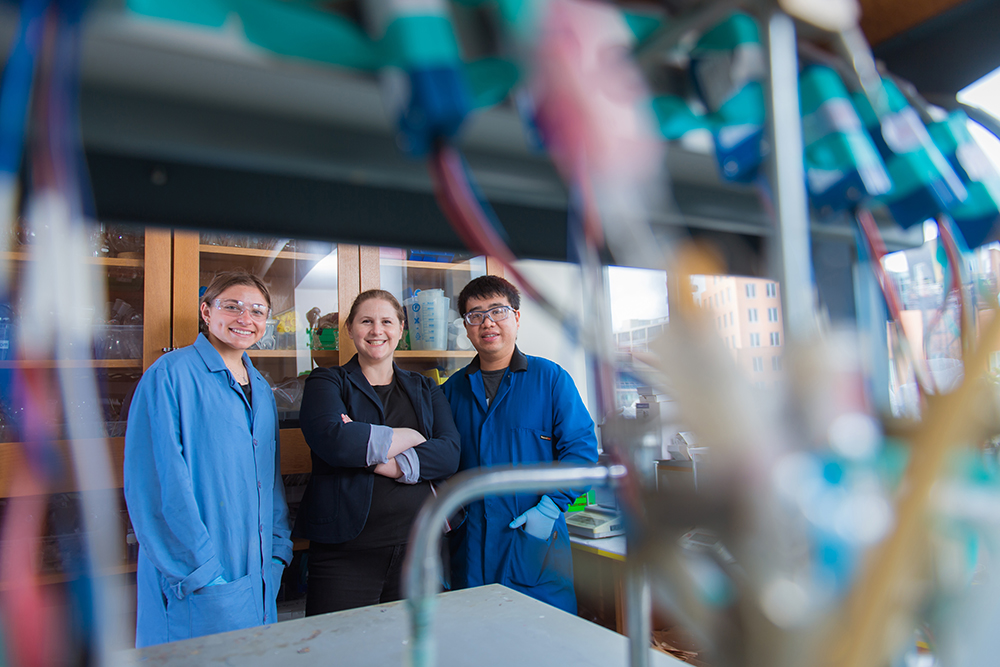

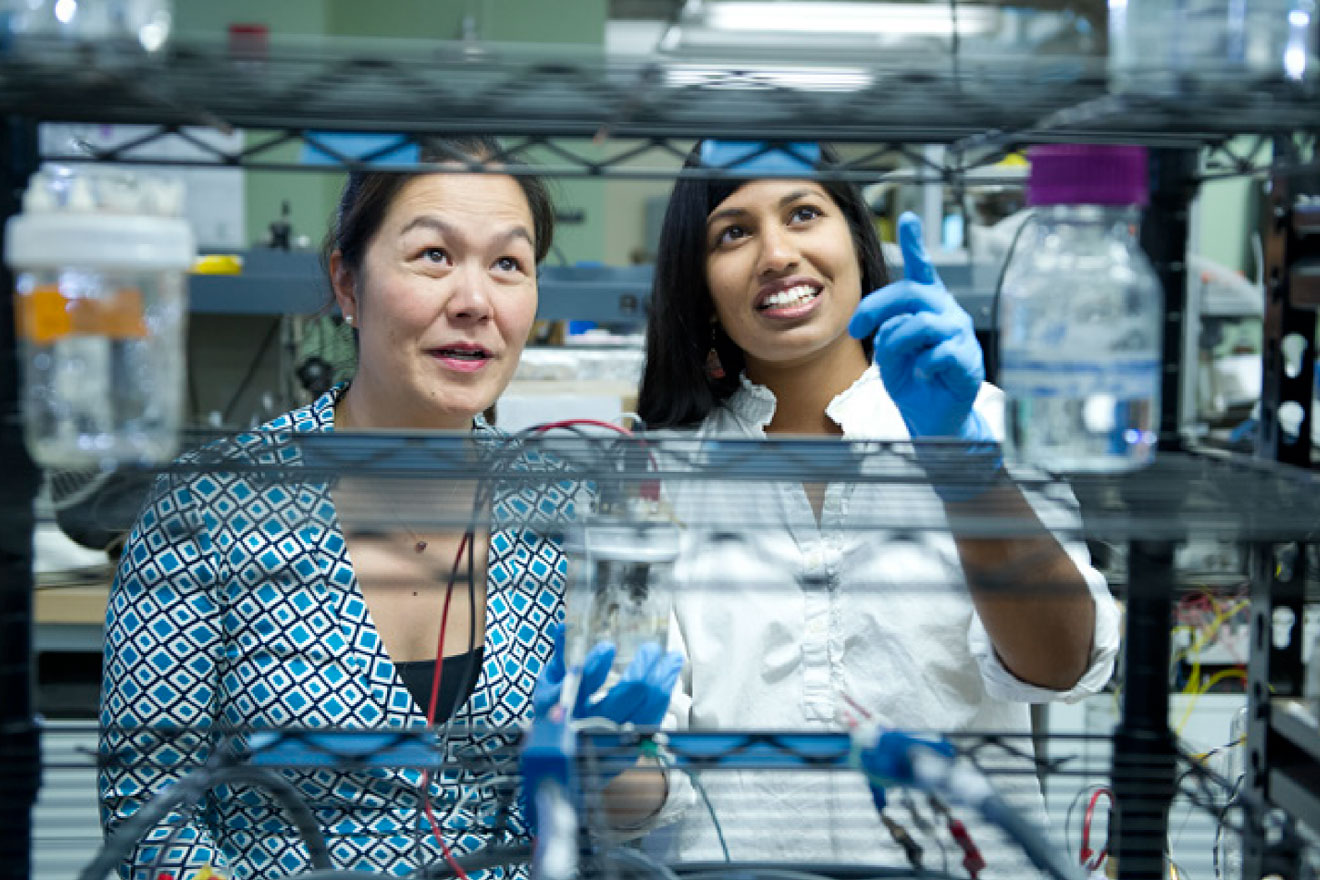

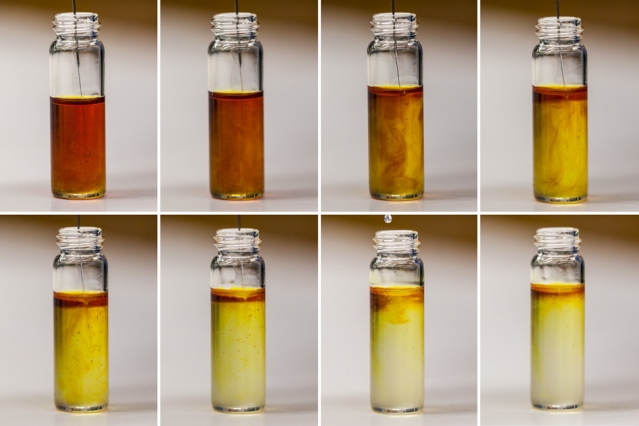

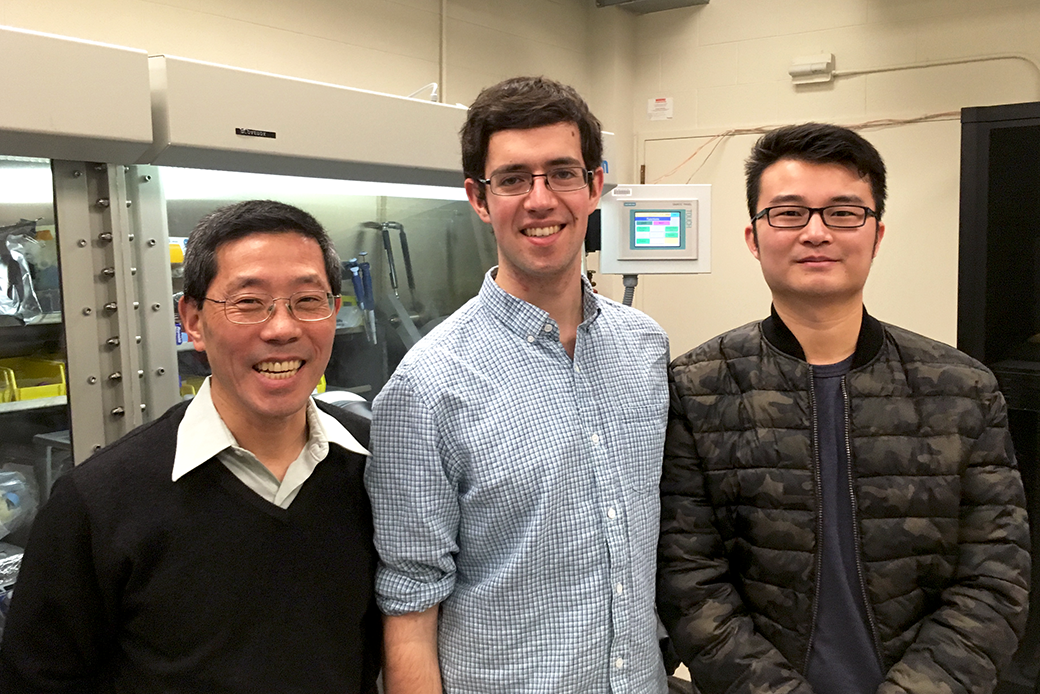

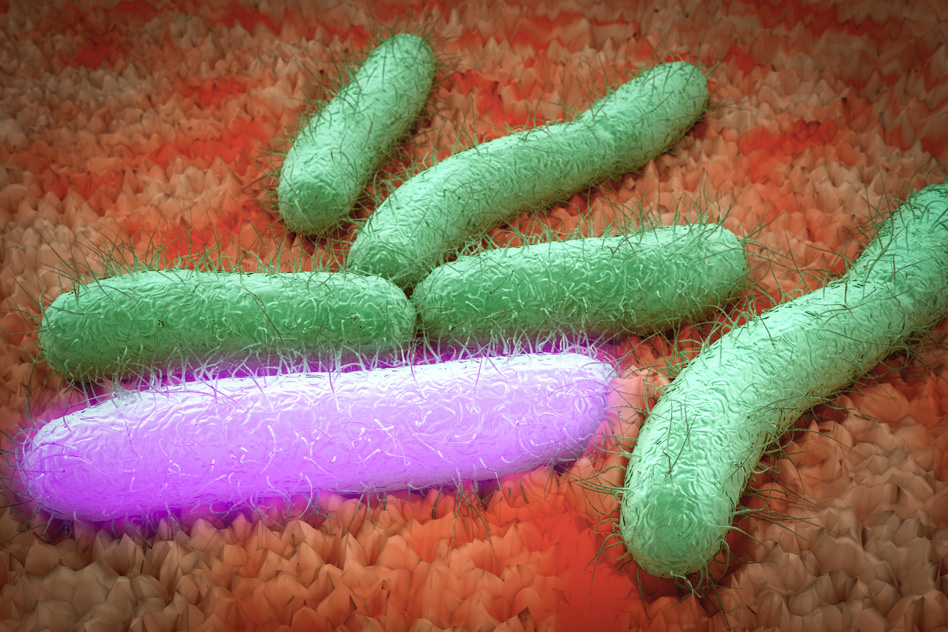

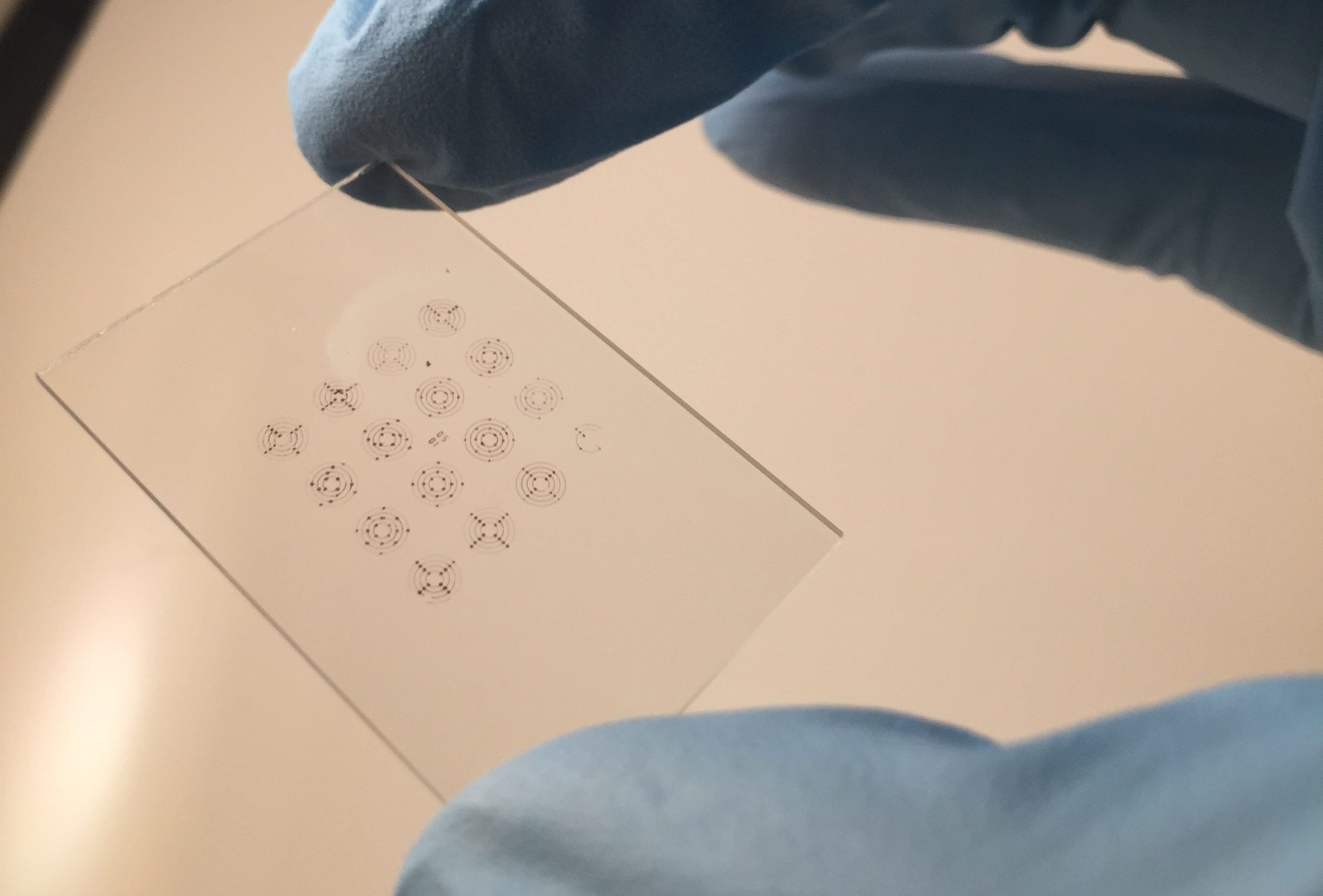

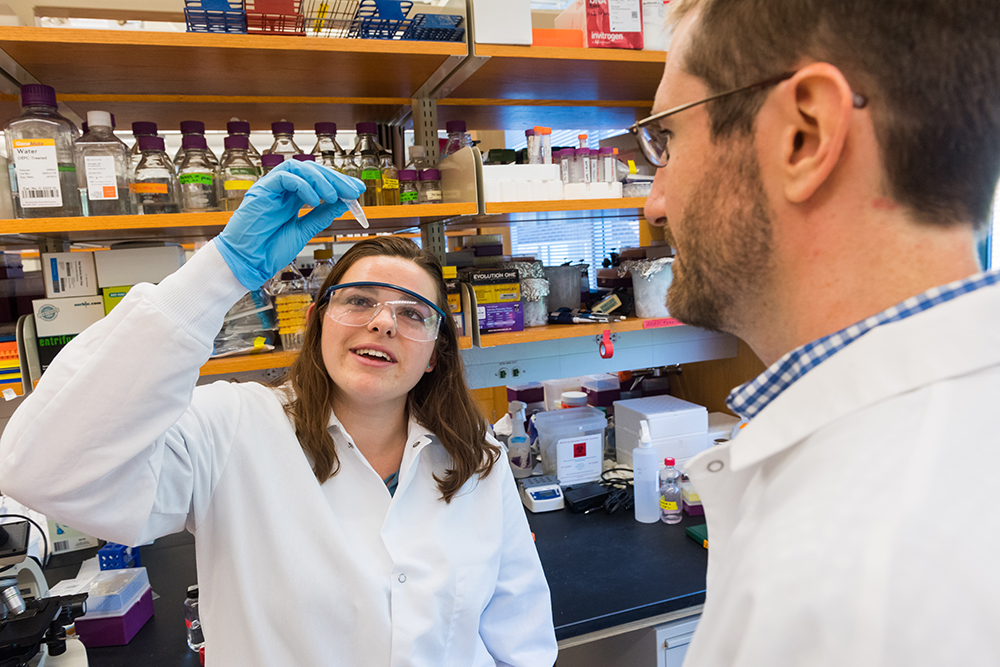

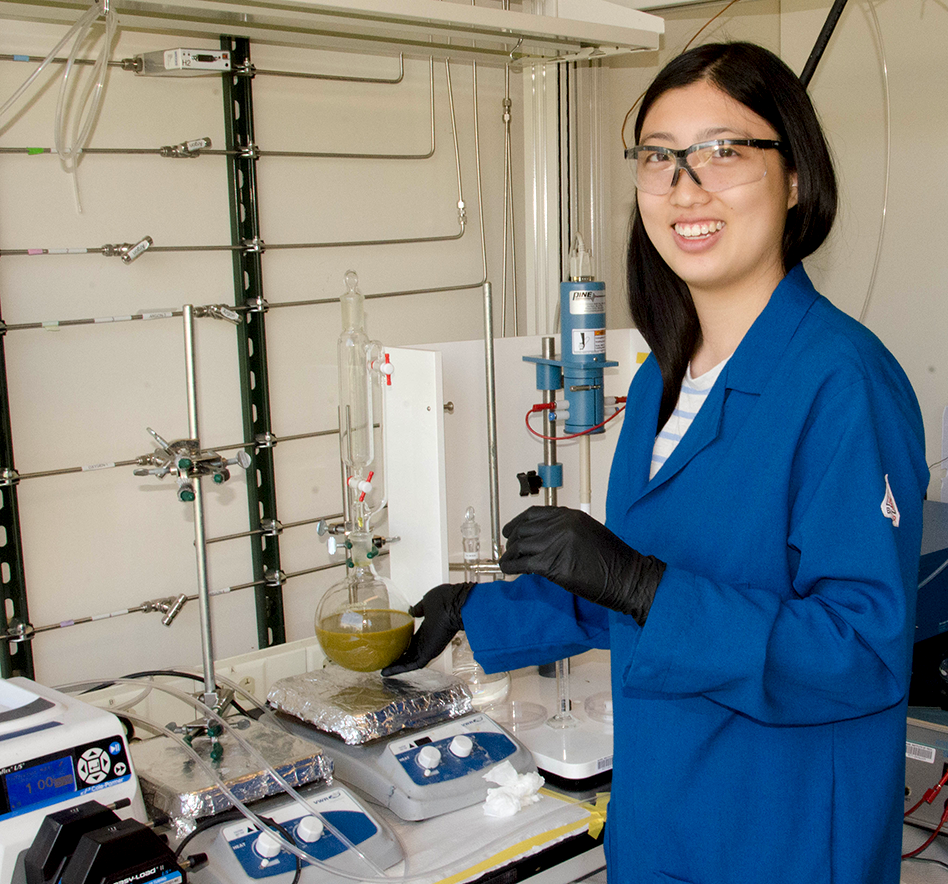

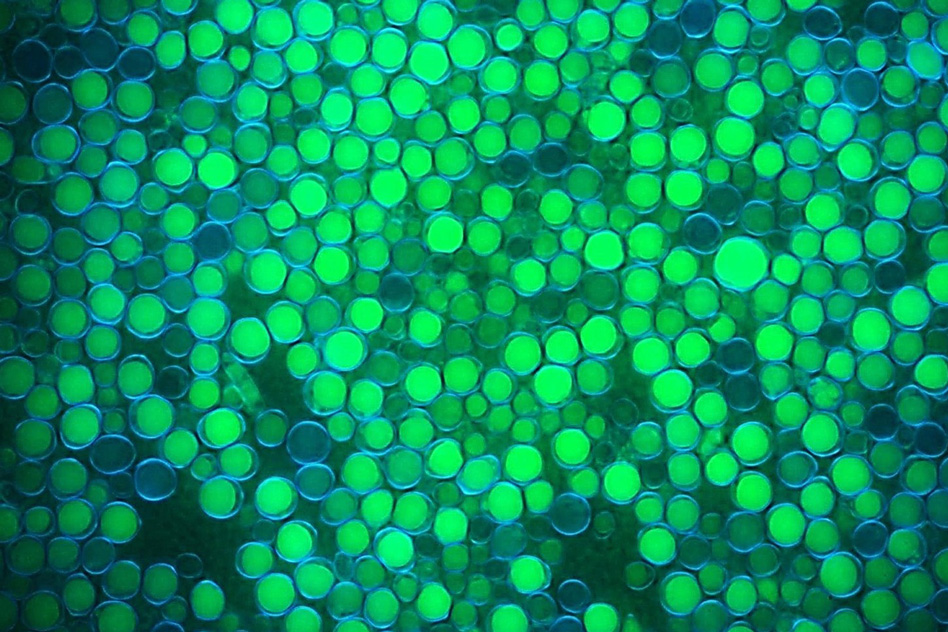

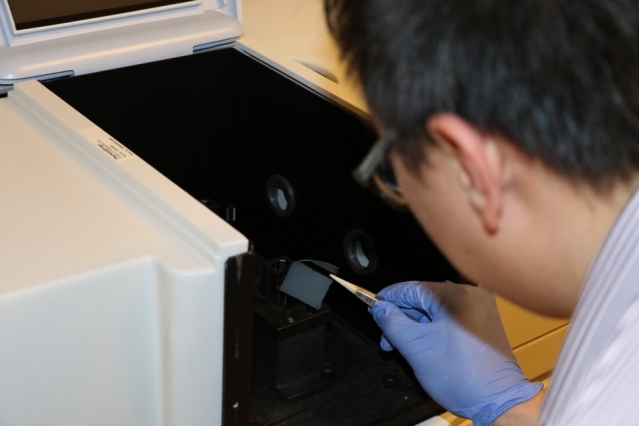

Two other articles in this issue focus on MIT projects that take novel approaches to ensuring the continued availability of clean-burning fossil fuels or of non-fossil replacement fuels. Researchers in mechanical and chemical engineering are working on a promising approach to converting heavy, sulfur-laden crude oil into clean, high-quality fuels including gasoline and diesel, and teams from MIT and the Whitehead Institute have demonstrated a simple but effective approach that could dramatically increase the productivity of yeast-based systems for making valuable biofuels such as ethanol and butanol.

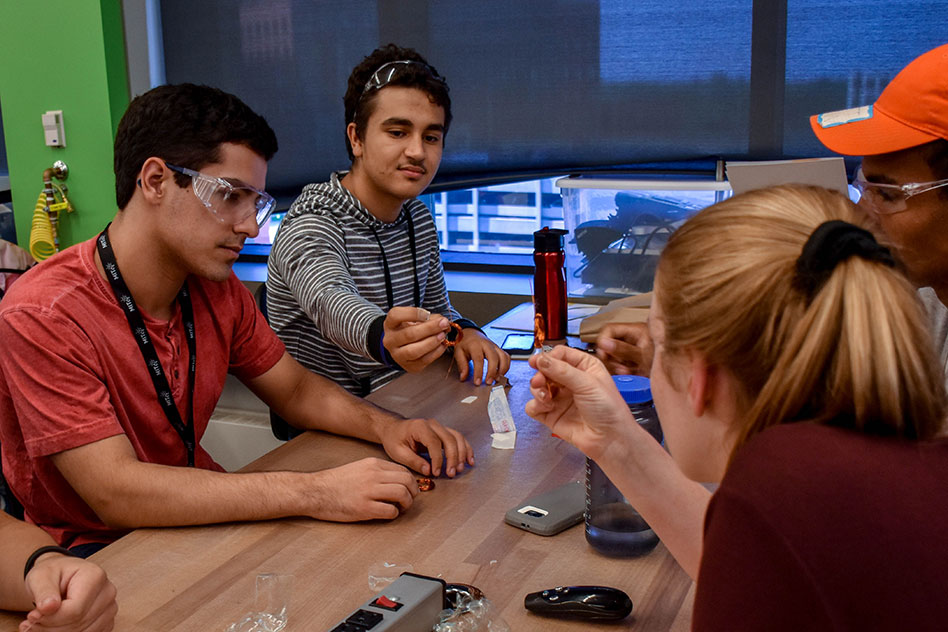

On campus, I’m pleased to report that we received a terrific response from faculty throughout the Institute to our call for proposals for undergraduate energy curriculum development, under a multi-year grant from the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. MITEI is pleased to support the development of five new classes and the significant revision of four others, with work starting this summer. The curriculum grants will build on the strength of the core domains of the Energy Studies Minor—energy science, technology, and social science—and will add important new content in the study of electrical grids from both technical and regulatory perspectives.

Finally, I was delighted to deliver the opening remarks at the 10th annual MIT Energy Conference in late February. Organized by the MIT Energy Club, this major event gathers the world’s energy leaders to share their expertise, and it always adds to the overwhelming sense of enthusiasm and responsibility felt across the MIT campus to solve the world’s energy challenges.

I hope you find this issue of Energy Futures informative and inspiring. MIT is special in the way it tackles society’s grand challenges. I am deeply indebted to all of you—our industrial partners, donors, alumni, and friends—for your support in this enterprise.

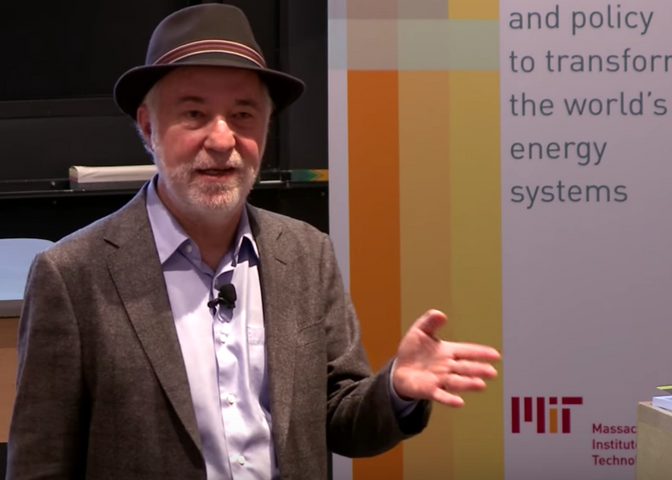

Professor Robert C. Armstrong

MITEI Director