Akarsh Aurora aspired “to be around people who are actually making the global energy transition happen,” he says. Sam Packman sought to “align his theoretical and computational interests to a clean energy project” with tangible impacts. Lauryn Kortman says she “really liked the idea of an in-depth research experience focused on an amazing energy source.”

These three MIT students found what they wanted in FUSars (fusion undergraduate scholars), a new program launched by the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC) to make meaningful fusion energy research accessible to undergraduates. Aurora, Kortman, and Packman are members of a cohort of 10 for the program’s inaugural run, which began spring semester 2023.

FUSars operates like a high-wattage UROP (MIT’s classic undergraduate research opportunity). The program requires a student commitment of 10 to 12 hours weekly on a research project during the course of an academic year, as well as participation in a for-credit seminar providing professional development, communication, and wellness support. Through this class and with the mentorship of graduate students, postdoctoral students, and research scientist advisors, students craft a publication-ready journal submission summarizing their research. Scholars who complete the entire year and submit a manuscript for review will receive double the ordinary UROP stipend—a payment that can reach $9,000.

“The opportunity just jumped out at me,” says Packman. “It was an offer I couldn’t refuse,” adds Aurora.

Building a workforce

“I kept hearing from students wanting to get into fusion, but they were very frustrated because there just wasn’t a pipeline for them to work at the PSFC,” says Michael Short, Class of ’42 Associate Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering (NSE) and associate director of the PSFC. As MIT’s largest lab, the PSFC bustles with research projects run by scientists and postdoctoral students. But since the PSFC isn’t a university department with educational obligations, it does not have the regular machinery in place to integrate undergraduate researchers.

This poses a problem not just for students but for the field of fusion energy, which holds the prospect of unlimited, carbon-free electricity. There are promising advances afoot: MIT and one of its partners, Commonwealth Fusion Systems, are developing a prototype for a compact commercial fusion energy reactor. The start of a fusion energy industry will require a steady infusion of skilled talent.

“We have to think about the workforce needs of fusion in the future and how to train that workforce,” says Rachel Shulman, who runs the FUSars program and co-instructs the FUSars class with Short. “Energy education needs to be thinking right now about what’s coming after solar, and that’s fusion.”

Short, who earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees at MIT, was himself the beneficiary of the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) at the PSFC. As a faculty member, he has become deeply engaged in building transformative research experiences for undergraduates. With FUSars, he hopes to give students a springboard into the field—with an eye to developing a diverse, highly trained, and zealous employee pool for a future fusion industry.

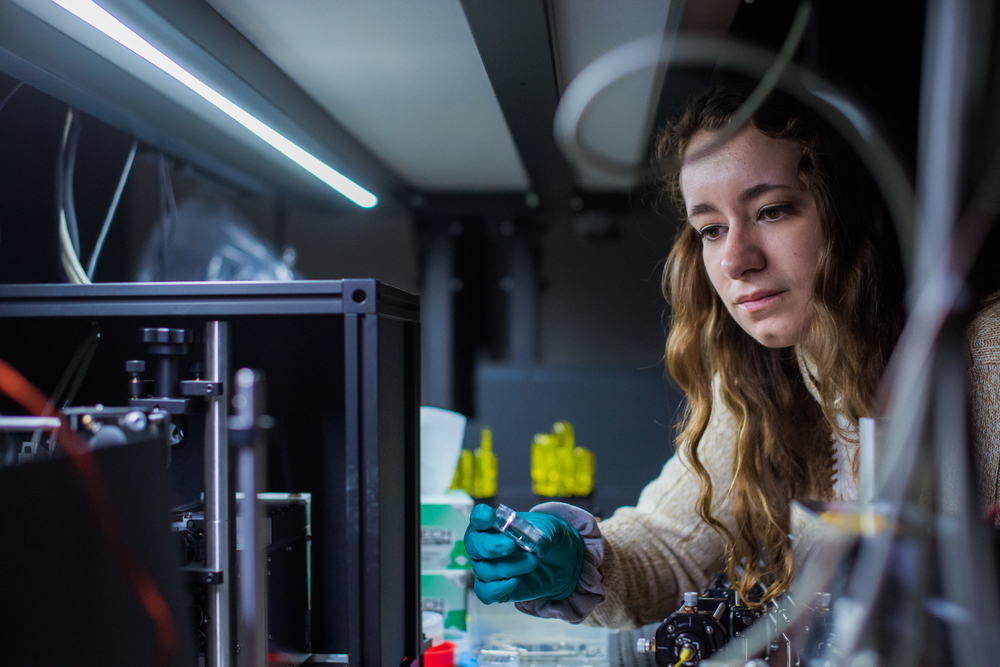

Through the FUSar program, MIT junior Lauryn Kortman measures the material properties of REBCO (rare-earth barium copper oxide), a high-temperature superconductor, before and after being exposed to proton irradiation. Here she analyzes a sample next to a transient grating spectroscopy machine, which can be used to nondestructively measure the bulk modulus, thermal diffusivity, and other key properties of a material. Credit: Gretchen Ertl

Taking a deep dive

Although these are early days for this initial group of FUSars, there is already a shared sense of purpose and enthusiasm. Chosen from 32 applicants in a whirlwind selection process—the program first convened in early February after crafting the experience over IAP—the students arrived with detailed research proposals and personal goals.

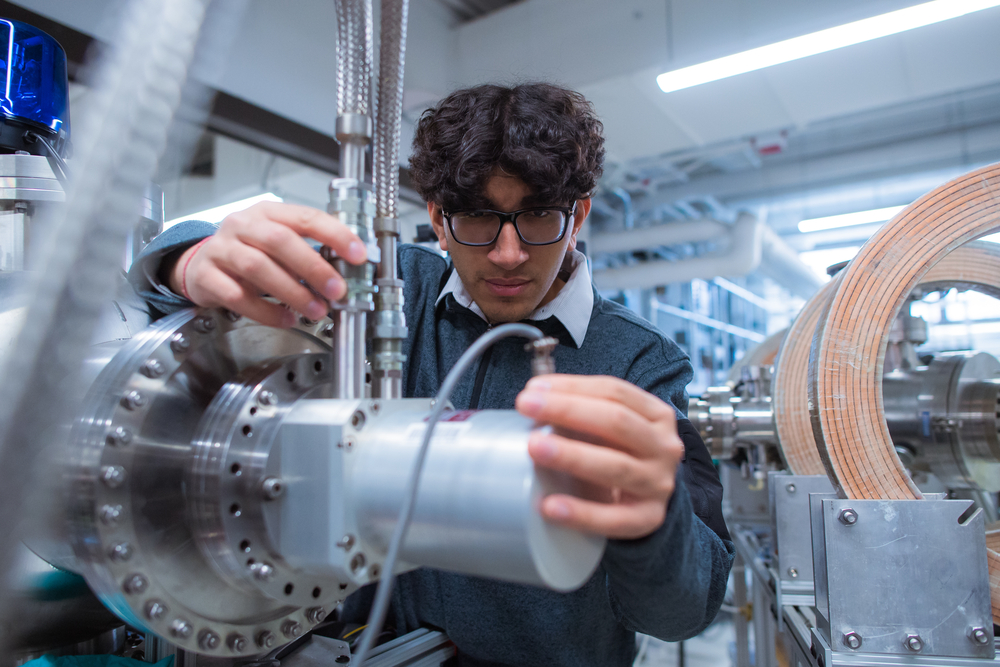

Aurora, a first-year majoring in mechanical engineering and artificial intelligence, became fixed on fusion while still in high school. Today he is investigating methods for increasing the availability, known as capacity factor, of fusion reactors. “This is key to the commercialization of fusion energy,” he says.

Packman, a first-year planning on a math and physics double major, is developing approaches to help simplify the computations involved in designing the complex geometries of solenoid induction heaters in fusion reactors.

“This project is more immersive than my last UROP, and requires more time, but I know what I’m doing here and how this fits into the broader goals of fusion science,” he says. “It’s cool that our project is going to lead to a tool that will actually be used.”

To accommodate the demands of their research projects, Shulman and Short discouraged students from taking on large academic loads.

Kortman, a junior majoring in materials science and engineering with a concentration in mechanical engineering, was eager to make room in her schedule for her project, which concerns the effects of radiation damage on superconducting magnets. A shorter research experience with the PSFC during the pandemic fired her determination to delve deeper and invest more time in fusion.

“It is very appealing and motivating to join people who have been working on this problem for decades, just as breakthroughs are coming through,” she says. “What I’m doing feels like it might be directly applicable to the development of an actual fusion reactor.”

MIT first-year Akarsh Aurora is investigating a special type of thin film tape made of rare-earth barium copper oxide, which is used in the superconductors that drive nuclear fusion, to understand how it behaves when exposed to neutron irradiation. Here he fixes the cryohead of a vacuum-sealed particle accelerator, which will be used to irradiate the tape and help his team glean insights about the material’s thermomechanical properties. Credit: Gretchen Ertl

Camaraderie and support

In the FUSar program, students aim to seize a sizeable stake in a multipronged research enterprise. “Here, if you have any hypotheses, you really get to pursue those because at the end of the day, the paper you write is yours,” says Aurora. “You can take ownership of what sort of discovery you’re making.”

Enabling students to make the most of their research experiences requires abundant support—and not just for the students. “We have a whole separate set of programming on mentoring the mentors, where we go over topics with postdocs like how to teach someone to write a research paper rather than write it for them and how to help a student through difficulties,” Shulman says.

The weekly student seminar, taught primarily by Short and Shulman, covers pragmatic matters essential to becoming a successful researcher—topics not always addressed directly or in the kind of detail that makes a difference. Topics include how to collaborate with lab mates, deal with a supervisor, find material in the MIT libraries, produce effective and persuasive research abstracts, and take time for self-care.

Kortman believes camaraderie will help the cohort through an intense year. “This is a tight-knit community that will be great for keeping us all motivated when we run into research issues,” she says. “Meeting weekly to see what other students are able to accomplish will encourage me in my own project.”

The seminar offerings have already attracted five additional participants outside the FUSars cohort. Adria Peterkin, a second-year graduate student in nuclear science and engineering, is sitting in to solidify her skills in scientific writing.

“I wanted a structured class to help me get good at abstracts and communicating with different audiences,” says Peterkin, who is investigating radiation’s impact on the molten salt used in fusion and advanced nuclear reactors. “There’s a lot of assumed knowledge coming in as a PhD student, and a program like FUSars is really useful to help level out that playing field, regardless of your background.”

Fusion research for all

Short would like FUSars to cast a wide net, capturing the interest of MIT undergraduates no matter their backgrounds or financial means. One way he hopes to achieve this end is with the support of private donors, who make possible premium stipends for fusion scholars.

“Many of our students are economically disadvantaged, on financial aid or supporting family back home, and need work that pays more than $15 an hour,” he says. This generous stipend may be critical, he says, to “flipping students from something else to fusion.”

Although this first FUSars class is composed of science and engineering students, Short envisions a cohort eventually drawn from the broad spectrum of MIT disciplines. “Fusion is not a nuclear-focused discipline anymore—it’s no longer just plasma physics and radiation,” he says. “We’re trying to make a power plant now, and it’s an all hands-on-deck kind of thing, involving policy and economics and other subjects.”

Although many are just getting started on their academic journeys, FUSar students believe this year will give them a strong push toward potential energy careers. “Fusion is the future of the energy transition and how we’re going to defeat climate change,” says Aurora. “I joined the program for a deep dive into the field, to help me decide whether I should invest the rest of my life to it.”

This article appears in the Spring 2023 issue of Energy Futures.