In 2016, at the huge Houston energy conference CERAWeek, MIT materials scientist Yet-Ming Chiang found himself talking to a Tesla executive about a thorny problem: how to store the output of solar panels and wind turbines for long durations.

Chiang, the Kyocera Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, and Mateo Jaramillo, a vice president at Tesla, knew that utilities lacked a cost-effective way to store renewable energy to cover peak levels of demand and to bridge the gaps during windless and cloudy days. They also knew that the scarcity of raw materials used in conventional energy storage devices needed to be addressed if renewables were ever going to displace fossil fuels on the grid at scale.

Energy storage technologies can facilitate access to renewable energy sources, boost the stability and reliability of power grids, and ultimately accelerate grid decarbonization. The global market for these systems—essentially large batteries—is expected to grow tremendously in the coming years. A study by the nonprofit LDES (Long Duration Energy Storage) Council pegs the long-duration energy storage market at between 80 and 140 terawatt-hours by 2040. “That’s a really big number,” Chiang notes. “Every ten people on the planet will need access to the equivalent of one EV [electric vehicle] battery to support their energy needs.”

In 2017, one year after they met in Houston, Chiang and Jaramillo joined forces to co-found Form Energy in Somerville, Massachusetts, with MIT graduates Marco Ferrara SM ’06, PhD ’08 and William Woodford PhD ’13, and energy storage veteran Ted Wiley.

“There is a burgeoning market for electrical energy storage because we want to achieve decarbonization as fast and as cost effectively as possible,” says Ferrara, Form’s senior vice president in charge of software and analytics.

Investors agreed. Over the next six years, Form Energy would raise more than $800 million in venture capital.

Bridging gaps

The simplest battery consists of an anode, a cathode, and an electrolyte. During discharge, with the help of the electrolyte, electrons flow from the negative anode to the positive cathode. During charge, external voltage reverses the process. The anode becomes the positive terminal, the cathode becomes the negative terminal, and electrons move back to where they started. Materials used for the anode, cathode, and electrolyte determine the battery’s weight, power, and cost “entitlement,” which is the total cost at the component level.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the use of lithium revolutionized batteries, making them smaller, lighter, and able to hold a charge for longer. The storage devices Form Energy has devised are rechargeable batteries based on iron, which has several advantages over lithium. A big one is cost.

Chiang once declared to the MIT Club of Northern California, “I love lithium-ion.” Two of the four MIT spinoffs Chiang founded center on innovative lithium-ion batteries. But at hundreds of dollars a kilowatt-hour and with a storage capacity typically measured in hours, lithium-ion was ill-suited for the use he now had in mind.

The approach Chiang envisioned had to be cost-effective enough to boost the attractiveness of renewables. Making solar and wind energy reliable enough for millions of customers meant storing it long enough to fill the gaps created by extreme weather conditions, grid outages, and when there is a lull in the wind or a few days of clouds.

To be competitive with legacy power plants, Chiang’s method had to come in at around $20 per kilowatt-hour of stored energy—one-tenth the cost of lithium-ion battery storage.

But how to transition from expensive batteries that store and discharge over a couple of hours to some as-yet-undefined, cheap, longer-duration technology?

“One big ball of iron”

That’s where Ferrara comes in. Ferrara has a PhD in nuclear engineering from MIT and a PhD in electrical engineering and computer science from the University of L’Aquila in his native Italy. In 2017, as a research affiliate at the MIT Department of Materials Science and Engineering, he worked with Chiang to model the grid’s need to manage renewables’ intermittency.

How intermittent depends on where you are. In the United States, for instance, there’s the windy Great Plains; the sun-drenched, relatively low-wind deserts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada; and the often-cloudy Pacific Northwest.

Ferrara, in collaboration with Professor Jessika Trancik of MIT’s Institute for Data, Systems, and Society and her MIT team, modeled four representative locations in the United States and concluded that energy storage with capacity costs below roughly $20/kilowatt-hour and discharge durations of multiple days would allow a wind-solar mix to provide cost-competitive, firm electricity in resource-abundant locations.

Now that they had a time frame, they turned their attention to materials. At the price point Form Energy was aiming for, lithium was out of the question. Chiang looked at plentiful and cheap sulfur. But a sulfur, sodium, water, and air battery had technical challenges.

Thomas Edison once used iron as an electrode, and iron-air batteries were first studied in the 1960s. They were too heavy to make good transportation batteries. But this time, Chiang and team were looking at a battery that sat on the ground, so weight didn’t matter. Their priorities were cost and availability.

“Iron is produced, mined, and processed on every continent,” Chiang says. “The Earth is one big ball of iron. We wouldn’t ever have to worry about even the most ambitious projections of how much storage that the world might use by mid-century.” If Form ever moves into the residential market, “it’ll be the safest battery you’ve ever parked at your house,” Chiang laughs. “Just iron, air, and water.”

Scientists call it reversible rusting. While discharging, the battery takes in oxygen and converts iron to rust. Applying an electrical current converts the rusty pellets back to iron, and the battery “breathes out” oxygen as it charges. “In chemical terms, you have iron, and it becomes iron hydroxide,” Chiang says. “That means electrons were extracted. You get those electrons to go through the external circuit, and now you have a battery.”

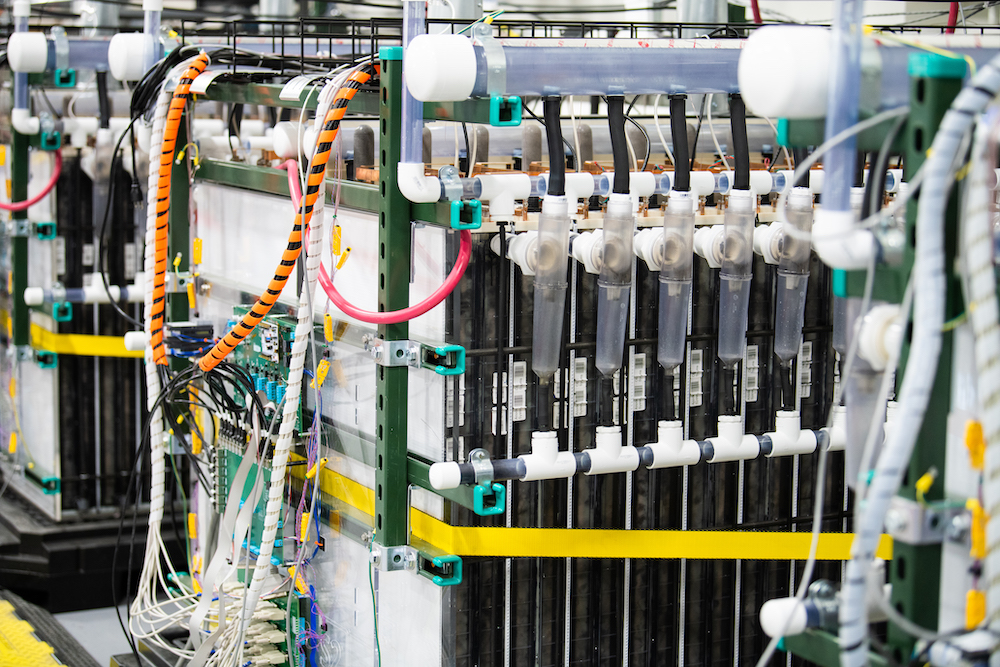

Form Energy’s battery modules are approximately the size of a washer and drier unit. They are stacked in 40-foot containers, and several containers are electrically connected with power conversion systems to build storage plants that can cover several acres.

Form Energy operates a 54,000-square-foot campus in the heart of the Bay Area where its full-scale battery systems are designed and tested at scale. Working in close collaboration with Form’s R&D team in Somerville, Massachusetts, and Advanced Manufacturing team in Eighty Four, Pennsylvania, Form’s Berkeley team ensures that the iron-air batteries are designed and validated to be manufactured at the system level. This photo shows a battery module being tested in Form’s Berkeley lab. Credit: Image courtesy of Form Energy

The right place at the right time

The modules don’t look or act like anything utilities have contracted for before.

That’s one of Form’s key challenges. “There is not widespread knowledge of needing these new tools for decarbonized grids,” Ferrara says. “That’s not the way utilities have typically planned. They’re looking at all the tools in the toolkit that exist today, which may not contemplate a multi-day energy storage asset.”

Form Energy’s customers are largely traditional power companies seeking to expand their portfolios of renewable electricity. Some are in the process of decommissioning coal plants and shifting to renewables.

Ferrara’s research pinpointing the need for very low-cost multi-day storage provides key data for power suppliers seeking to determine the most cost-effective way to integrate more renewable energy.

Using the same modeling techniques, Ferrara and team show potential customers how the technology fits in with their existing system, how it competes with other technologies, and how, in some cases, it can operate synergistically with other storage technologies.

“They may need a portfolio of storage technologies to fully balance renewables on different timescales of intermittency,” he says. But other than the technology developed at Form, “there isn’t much out there, certainly not within the cost entitlement of what we’re bringing to market.” Thanks to Chiang and Jaramillo’s chance encounter in Houston, Form has a several-year lead on other companies working to address this challenge.

In June 2023, Form Energy closed its biggest deal to date for a single project: Georgia Power’s order for a 15-megawatt/1,500-megawatt-hour system. That order brings Form’s total amount of energy storage under contracts with utility customers to 40 megawatts/4 gigawatt-hours. To meet the demand, Form is building a new commercial-scale battery manufacturing facility in West Virginia.

The fact that Form Energy is creating jobs in an area that lost more than ten thousand steel jobs over the past decade is not lost on Chiang. “And these new jobs are in clean tech. It’s super exciting to me personally to be doing something that benefits communities outside of our traditional technology centers.

“This is the right time for so many reasons,” Chiang says. He says he and his Form Energy co-founders feel “tremendous urgency to get these batteries out into the world.”

This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue of Energy Futures.